Writing a compelling lab report introduction doesn’t have to be overwhelming. Whether you’re a biology student tackling your first experiment or a chemistry major refining your skills, mastering this crucial section can transform your entire report. At Study Watches, we understand the time constraints students face, which is why we’ve compiled these proven strategies to help you craft effective introductions quickly and efficiently.

The introduction serves as the foundation of your lab report, setting the stage for everything that follows. It’s where you capture your reader’s attention, establish context, and outline your experimental approach. Many students struggle with this section because they’re unsure where to begin or how much detail to include.

Learning how to start a lab report introduction effectively requires understanding its core components and following a structured approach. Once you grasp these fundamentals, you can streamline your writing process and produce high-quality introductions consistently.

Understanding the Purpose of Your Lab Report Introduction

The introduction accomplishes several critical objectives simultaneously. First, it provides essential background information that helps readers understand the scientific context of your experiment. This includes relevant theories, previous research findings, and the scientific principles underlying your investigation.

Second, your introduction establishes the rationale for conducting the experiment. You need to explain why this particular investigation matters and how it contributes to existing scientific knowledge. This justification helps readers appreciate the significance of your work.

Finally, the introduction presents your hypothesis or research question clearly. This statement guides the entire experiment and gives readers a clear expectation of what you’re trying to prove or discover.

Essential Components Every Introduction Must Include

Background Information and Context

Start with broader scientific concepts before narrowing down to your specific experiment. This approach helps readers understand how your work fits into the larger scientific landscape. Include relevant theories, laws, or principles that directly relate to your investigation.

Literature Review Elements

Incorporate findings from previous studies that relate to your experiment. You don’t need an exhaustive literature review, but mentioning key research helps establish credibility and shows you understand the existing knowledge base.

Problem Statement or Research Gap

Identify what specific question your experiment addresses. This might be testing a known principle under different conditions, exploring an unexplored variable, or verifying previous results. Clearly articulating this problem helps justify your experimental approach.

Hypothesis Statement

Present your prediction about the experiment’s outcome based on scientific reasoning. A well-crafted hypothesis should be testable, specific, and grounded in scientific theory. It should directly connect to your experimental design and methodology.

Quick Strategies for Efficient Introduction Writing

The Funnel Approach

Structure your introduction like an inverted funnel, starting broad and becoming increasingly specific. Begin with general scientific principles, then narrow down to your specific research area, and finally focus on your particular experiment. This logical flow helps readers follow your reasoning naturally.

Template-Based Writing

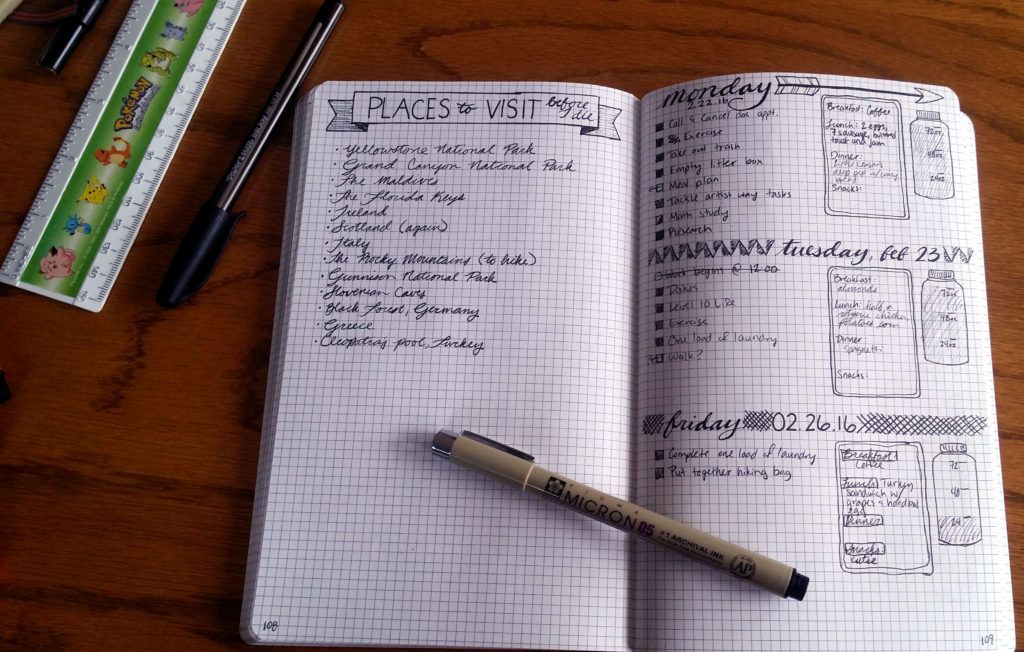

Develop a reliable template that you can adapt for different experiments. A typical structure might include: opening context paragraph, literature background, problem identification, hypothesis statement, and brief methodology overview. Having this framework speeds up your writing process significantly.

Time-Boxed Writing Sessions

Set specific time limits for each section of your introduction. Spend 10-15 minutes on background research, 15-20 minutes on the first draft, and 10 minutes on revision. This approach prevents perfectionism from slowing you down while ensuring adequate attention to each component.

Research Techniques That Save Time

Targeted Literature Searches

Use specific keywords related to your experiment to find relevant sources quickly. Focus on recent peer-reviewed articles and authoritative textbooks rather than spending time on outdated or unreliable sources. Academic databases like PubMed, JSTOR, or Google Scholar can help you locate quality references efficiently.

Note-Taking Systems

Develop a systematic approach to recording important information from your sources. Create templates that capture key details like methodology, findings, and relevance to your experiment. This organization makes it easier to synthesize information when writing your introduction.

Source Evaluation Shortcuts

Learn to quickly assess source quality by examining publication dates, journal reputation, author credentials, and citation counts. This skill helps you prioritize the most valuable sources and avoid wasting time on low-quality materials.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Overly Detailed Background Information

While context is important, avoid turning your introduction into a comprehensive textbook chapter. Include only information that directly relates to understanding your experiment. Excessive detail can overwhelm readers and obscure your main points.

Vague or Missing Hypothesis Statements

A weak hypothesis undermines your entire report. Ensure your hypothesis is specific, testable, and clearly stated. Avoid vague language like “we expect interesting results” and instead provide concrete, measurable predictions.

Inadequate Connection Between Sections

Each paragraph should logically connect to the next, creating a smooth narrative flow. Use transition sentences to link ideas and help readers follow your reasoning from general concepts to your specific investigation.

Writing Techniques for Clarity and Flow

Active Voice Usage

Employ active voice whenever possible to create more direct, engaging sentences. Instead of “The experiment was conducted,” write “We conducted the experiment.” Active voice typically produces clearer, more concise writing.

Varied Sentence Structure

Mix short and long sentences to create rhythm and maintain reader interest. Short sentences work well for key points, while longer sentences can provide detailed explanations or connect multiple ideas.

Strategic Keyword Placement

Naturally incorporate relevant scientific terminology throughout your introduction. This demonstrates your understanding of the subject matter while improving the searchability and professional tone of your report.

Revision and Polish Strategies

Structural Review Process

After completing your first draft, step back and evaluate the overall structure. Ensure each paragraph serves a clear purpose and contributes to building your argument. Remove redundant information and strengthen weak connections between ideas.

Clarity Enhancement Techniques

Read your introduction aloud to identify awkward phrasing or unclear explanations. Complex scientific concepts should be explained clearly enough for someone outside your specific field to understand the basic principles involved.

Peer Review Benefits

Having classmates or study group members review your introduction can reveal unclear sections or missing information. Fresh eyes often catch issues that you might overlook after working on the same text extensively.

Technology Tools for Faster Writing

Reference Management Software

Tools like Zotero, Mendeley, or EndNote can dramatically speed up citation formatting and bibliography creation. These programs automatically format references according to different style guides and help you organize your source materials efficiently.

Grammar and Style Checkers

Applications like Grammarly or Hemingway Editor can help identify grammatical errors, awkward phrasing, and overly complex sentences. While these tools aren’t perfect, they can catch common mistakes and suggest improvements.

Outline Generation Tools

Mind mapping software or simple outline templates can help you organize your thoughts before writing. Creating a clear structure beforehand often results in faster, more coherent writing.

Advanced Tips for Expert-Level Introductions

Strategic Citation Integration

Weave citations naturally into your narrative rather than simply listing them at the end of paragraphs. This integration shows deeper engagement with the literature and creates more sophisticated arguments.

Compelling Opening Strategies

Start with an intriguing fact, relevant quote, or thought-provoking question related to your experiment. This approach immediately engages readers and establishes the importance of your research topic.

Seamless Transition to Methods

End your introduction with a sentence that naturally leads into your methodology section. This transition might mention your experimental approach or briefly preview your investigation strategy.

Conclusion

Mastering the art of writing lab report introductions quickly requires understanding the essential components, developing efficient research strategies, and practicing systematic writing approaches. By implementing these techniques, you can produce high-quality introductions that effectively set up your experiments while saving valuable time.

Remember that the key lies in balancing thoroughness with efficiency. Focus on including only relevant information, maintaining clear logical flow, and presenting your hypothesis prominently. With practice, these strategies will become second nature, allowing you to tackle even complex experimental introductions with confidence.

The most successful students develop personalized systems that work for their learning style and time constraints. Experiment with different approaches from this guide to find the combination that works best for your specific needs and academic requirements.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long should a lab report introduction be? A typical lab report introduction should be 1-2 pages or roughly 300-500 words, depending on the complexity of your experiment and your instructor’s requirements. Focus on including all essential components rather than meeting a specific word count.

Should I include my results or conclusions in the introduction? No, the introduction should only present background information, your hypothesis, and experimental rationale. Save results, analysis, and conclusions for their respective sections to maintain proper report structure.

How many sources should I cite in my introduction? Include 3-5 relevant, high-quality sources for most undergraduate lab reports. Graduate-level work might require more extensive literature review, but focus on source quality rather than quantity.

Can I use first person in my lab report introduction? This depends on your instructor’s preferences and institutional guidelines. Some allow first person (“We hypothesized that…”), while others prefer passive voice (“It was hypothesized that…”). Check your assignment requirements.

What’s the difference between a hypothesis and a prediction? A hypothesis is a testable explanation for a phenomenon based on scientific theory, while a prediction is a specific, measurable outcome you expect from your experiment. Your hypothesis should lead logically to your prediction.

Read More:

Why is architecture so important in school buildings?